“Juglans [walnut] has a different pattern,” says Krebs. The spread of pollen from these trees is less clearly associated with the rise and fall of the Roman empire, he and his colleagues found. Its distribution around Europe had already increased before the arrival of the Romans, perhaps pointing to the ancient Greeks and other pre-Roman communities as playing a role.

But while the Romans can perhaps take credit for spreading the sweet chestnut around mainland Europe, some separate research suggests they were not behind the arrival of these trees in Britain. Although the Romans have previously been credited with bringing sweet chestnuts to the British isles – where they are still a key part of modern woodlands – research by scientists at the University of Gloucestershire in the UK found the trees were probably introduced to the island later.

This speedy regrowth came in handy given the Romans’ constant need for raw materials for their military expansion

Sweet chestnut trees can be striking features of the landscape. They can grow up to 35m (115ft) tall and can live for up to 1,000 years in some locations. Most of those alive today will not have been planted by the Romans, but many will be descendants or even cuttings taken from those that ancient Roman legionnaires and foresters brought with them to the far-flung corners of the empire. The oldest known sweet chestnut tree in the world is found in Sicily, Italy, and is thought to be up to 4,000 years old.

Wood for fortresses

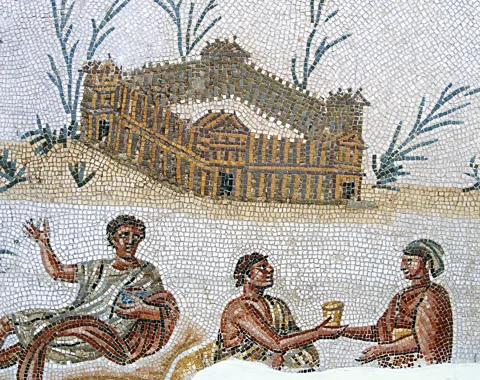

Why did the Romans so favour the sweet chestnut tree? According to Krebs, they did not tend to value the fruit much – in Roman culture, it was portrayed as a rustic food of poor, rural people in Roman society, such as shepherds. But the Roman elites did appreciate sweet chestnut’s ability to quickly sprout new poles when cut back, a practice known as coppicing. This speedy regrowth came in handy given the Romans’ constant need for raw materials for their military expansion.

“Ancient texts show that the Romans were very interested in Castanea, especially for its resprouting capacity,” he says. “When you cut it, it resprouts very fast and produces a lot of poles that are naturally very high in tannins, which makes the wood resistant and long-lasting. You can cut this wood and use it for building fortresses, for any kind of construction, and it quickly sprouts again.”

Coppicing can also have a rejuvenating effect on the chestnut tree, even after decades of neglect.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Ticino, chestnut trees became more and more dominant under the Romans, according to the pollen record. They remained popular even after the Roman Empire fell, Krebs says.

One explanation for this is that locals had learned to plant and care for the tree from the Romans, and then came to appreciate chestnuts as a nourishing, easy-to-grow food – by the Middle Ages, they had become a staple food in many parts of Europe. The chestnuts, for example, could be dried and ground into flour. Mountain communities would also have welcomed the fact that the trees thrived even on rocky slopes, where many other fruit trees and crops struggled, Krebs adds.

“The Romans’ achievement was to bring these skills from far away, to enable communication between people and spread knowledge,” he says. “But the real work of planting the chestnut tree orchards was probably done by local populations.”

When they are cultivated in an orchard for their fruit, sweet chestnut trees benefits from management such as pruning dead or diseased wood, as well as the lack of competition, all of which prolong their life, Krebs says: “In an orchard, there’s just the chestnut tree and the meadow below, it’s like a luxury residence for the tree. Whereas when the orchard is abandoned, competitor trees arrive and take over.”